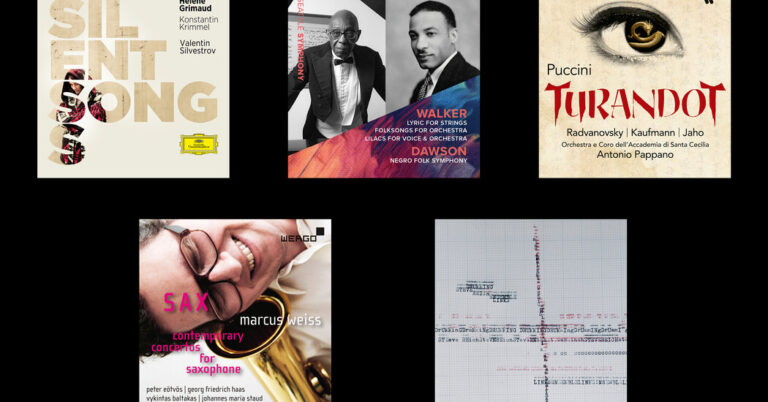

Walker & Dawson: Orchestral Works

Nicole Cabell, soprano; Seattle Symphony Orchestra, Asher Fisch and Roderick Cox, conductors (Seattle Symphony Media)

Not all that long ago, the Seattle Symphony’s label was one of the most interesting around. Ludovic Morlot, the ensemble’s music director from 2011 to 2019, is a musician of broad tastes, and his recordings drew acclaim for their programming: He did a Dutilleux cycle, offered plenty of Ives and got creative with the classics, pairing Dvorak with Varèse. Thomas Dausgaard, who had an oddly brief tenure as Morlot’s successor, took the label in a rather less inventive direction, so it’s good to see the orchestra returning to form here.

George Walker has been the subject of recent releases from the Cleveland Orchestra and the National Symphony Orchestra, and these performances under the guest conductor Asher Fisch — a poignant, unsentimental “Lyric for Strings,” a slightly slack “Folksongs for Orchestra” and a “Lilacs” in which the soprano Nicole Cabell is searingly intense — are equally worth hearing.

More impressive, though, is Roderick Cox’s spirited take on William L. Dawson’s “Negro Folk Symphony,” a piece that — like the symphonies of his contemporaries, Florence Price and William Grant Still — deserves better than the scant attention major ensembles have paid it since Leopold Stokowski led the premiere in 1934. At its core is a trudging, pained, slow movement, “Hope in the Night,” in which dreams of liberation struggle to become realities amid the lasting traumas of slavery. Cox and the Seattle players give it great dignity. DAVID ALLEN

Puccini: ‘Turandot’

Sondra Radvanovsky, Jonas Kaufmann and Ermonela Jaho, singers; Orchestra and Chorus of the Accademia Nazionale di Santa Cecilia; Antonio Pappano, conductor (Warner)

Grand scale and high costs have made it unusual to set down full operas in the studio, as opposed to capturing live performances. But the conductor Antonio Pappano and the superb orchestra and lively chorus of the Accademia Nazionale di Santa Cecilia, in Rome, have now followed their atmospheric 2015 studio version of “Aida” with a similarly hyperdetailed studio “Turandot.”

The playing is vivid — strings lush and articulate, winds restrained, brasses secure — with a precision and transparency that emphasize Puccini’s debt to the adventurous instrumental textures, harmonies and gauzy exoticism of Stravinsky, Debussy and Strauss. But with often quite slow tempos, Pappano revels in pure sound more than urgent drama. And while it is fascinating to get a rare hearing of Franco Alfano’s full version of the work’s ending (which Puccini left incomplete at his death in 1924) rather than the curtailed, crushingly unsubtle Alfano conclusion sanctioned by Toscanini, it all feels exaggeratedly drawn out.

More on N.Y.C. Theater, Music and Dance This Spring

In the title role, Sondra Radvanovsky is imposing — and unafraid, in the second act, to sound unsympathetic, even ugly: sneering, curt, sour. Some of her high notes are intense and resonant, but her vibrato can be wild and her very soft and low singing, uncertain. As Prince Calaf, the tenor Jonas Kaufmann’s dark, hooded tone can make it seem as if he needs to force the sound to emerge, an effect that is sometimes exciting and sometimes simply squeezed. The soprano Ermonelo Jaho renders the doomed Liù with her characteristic moving fragility, her voice trembling with emotion. Overall, the recording slides between hypnotic and somnolent. ZACHARY WOOLFE

‘SAX — Contemporary Concertos for Saxophone’

Marcus Weiss (Wergo)

In the liner notes for this smartly programmed release, the saxophonist Marcus Weiss writes that there aren’t many concerto highlights in the repertoire for his instrument. But he does nominate Peter Eotvos’s “Focus” as one such standout.

Alongside the WDR Symphony Orchestra and the conductor Elena Schwarz, Weiss makes a strong argument for the piece. After a flurry of Rimsky-Korsakov-style bumblebee-riffing in the opening seconds, Eotvos’s concerto quickly gets down to original-sounding business: The first movement puts Weiss on tenor and gives him a generous amount of thematically convincing soloing to execute next to the orchestra’s passages of muted-brass swagger and gliding-then-plucked strings. Over the work’s four movements, Eotvos does something as charming as it is hard to pull off: His European concerto doffs its cap to American jazz’s irrevocable redefinition of the saxophone, all without sounding cowed or trite.

Up next is the Concerto for Baritone Saxophone and Orchestra, by the veteran spectralist Georg Friedrich Haas. While more consistently fascinated by play with multiphonics than Eotvos, Haas here also has the satisfying build of a great big band piece. (Enjoy the broad arc that finishes with a grand swell over the first five minutes.) Then come a pair of works by younger composers that, to my ears, fall somewhat short of the high standard set by the senior figures on this bill — but Weiss advocates those works strongly as well, illustrating a bright present and promising future for saxophone concertos. SETH COLTER WALLS

Silvestrov: ‘Silent Songs’

Konstantin Krimmel, baritone; Hélène Grimaud, piano (Deutsche Grammophon)

The French pianist Hélène Grimaud has wanted to perform Valentin Silvestrov’s “Silent Songs” since receiving a recording as a gift nearly 20 years ago. It’s easy to understand why: They are astonishingly beautiful and criminally underperformed.

Silvestrov has called the 24-song cycle — a nearly two-hour work about grave mistakes, drowned sorrows and a hostile world — “silence set to music.” He envisioned it as a long, single, quiet song.

Sergey Yakovenko and Ilya Scheps’s foundational recording from 1986 — the one given to Grimaud — approaches soundlessness with its tense, whispered regret. Yakovenko sings in a skeletal hush, and the music aches like nostalgia that is only a memory of past failures.

Grimaud’s new album of excerpts with the baritone Konstantin Krimmel, recorded live in Silvestrov’s presence after he fled the war in Ukraine, isn’t like that. It’s practically lush by comparison. Gorgeous melodies unspool like ever-elongating ribbons. The piano doubles the voice a lot, requiring conscientious coordination between the performers at exposed dynamics, and their care conveys a gentleness they find at the work’s heart.

Silvestrov’s instructions call for a baritone that sounds like a tenor, and Krimmel, with his clarified timbre and gossamer top notes, fits the brief exquisitely. His voice — vulnerable, pliable, at times crooning — has the bloom of youth. Grimaud’s playing, softly golden and delicately smooth, tethers the melodies, allowing them to billow freely without floating away. In their hands, these autumnal songs have the warmth of well-tended embers. OUSSAMA ZAHR

Steve Reich: ‘Drumming’

Ensemble Links (LINKS)

Steve Reich’s composing career is littered with milestones, but few are more significant than “Drumming” (1971). It showed that his experiments with phasing processes weren’t just the stuff of tape and electronics, but could be transferred to live instrumentation, and compellingly so. There are fewer recordings than you might expect of a piece of its stature, but each one has thrown light on the work’s ritualistic quality, shimmering sound world or hard-hitting energy.

The newest entry, by the superb French group Ensemble Links, has something important to say about all of these aspects of “Drumming.” Aided by gloriously clear sound, this account is crisp, exact and light on its feet. In a fast reading, just over 50 minutes, the performers make each tiny change in rhythm and instrumentation land both musically and emotionally. Just as important, they don’t miss the forest for the trees: Control over dynamics and pacing is so sure that you hear and feel all those tiny variations as steps in a vast unfolding of a single process. The Links players also nail the balances between the various instrumental groups, nowhere better than in the final section, a rush of sound and pulsation that thrills even now, more than half a century after its first sounding. DAVID WEININGER